The Nicolson House : Report on the 1982 Archaeological Investigations

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 228

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

The Nicolson House

Report on the 1982 Archaeological Investigations

Archaeological Report

by

Patricia Samford

Office of Archaeological Excavation

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

1986

Abstract

The Nicolson House, owned by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, was built circa 1751-1753 on what was, at that time, the outskirts of Williamsburg. It began as a small three bay structure, home to Robert Nicolson, tailor and merchant. Around 1766, as Nicolson's family and business grew, he added a two bay extension on the western end of the house, and moved his business to Duke of Gloucester Street. Structurally, the house has essentially remained the same for the last 200 years. It was purchased by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1965.

The 1982 archaeological excavation around the Nicolson House was precipitated by plans to waterproof the underground foundation walls. The excavation, conducted from January to May, revealed formerly unknown architectural information about structural repairs, fence lines, and outbuildings adjacent to the house. Due to the limited scope of the project, the amount of information actually recovered was limited to those changes which occurred immediately adjacent to the house. Included in this report is analysis of the archaeological features which span the two hundred year period of the house's occupation and those artifacts recovered during the excavation.

| LIST OF FIGURES | iii | |

| LIST OF TABLES | iv | |

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | v | |

| CHAPTER 1. | INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| CHAPTER 2. | HOUSE HISTORY | 8 |

| CHAPTER 3. | FIELD METHODS AND ANALYSIS | 17 |

| CHAPTER 4. | ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESULTS | 19 |

| A. | Nicolson House Architectural Features | 20 |

| B. | Landscape Features | 35 |

| C. | Miscellaneous Features | 50 |

| CHAPTER 5. | CONCLUSION | 52 |

| CHAPTER 6. | BIBLIOGRAPHY | 55 |

| APPENDIX 1. | FEATURE LIST | 60 |

| APPENDIX 2. | FAUNAL ANALYSIS by Joanne Gaynor | 63 |

| Figure 1. | Photo of Nicolson House, South Façade | 2 |

| 2. | Frenchman's Map, 1781 | 3 |

| 3. | Detail of Frenchman's Map showing Nicolson House | 4 |

| 4. | Desandrouins Map | 5 |

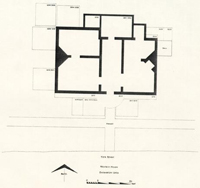

| 5. | Construction Sequence of Nicolson House | 11 |

| 6. | Photograph of Nicolson House, early 20th Century | 16 |

| 7. | Plan of 1982 Excavation Units | 18 |

| 8. | Delftware Punch Bowl Found in Builder's Trench | 21 |

| 9. | Northwest Foundation Wall Showing Repairs | 23 |

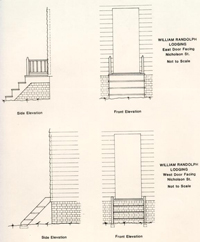

| 10. | Possible Front Porch Reconstructions | 25 |

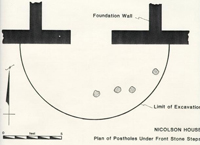

| 11. | Plan of Post-holes under front Stone Steps | 26 |

| 12. | Three Periods of Back Porch Construction | 28 |

| 13. | Nicolson House, North Façade, 1933 | 29 |

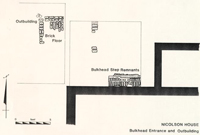

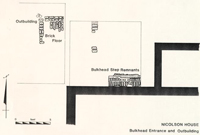

| 14. | Plan of Bulkhead Entrance and Outbuilding Remains | 31 |

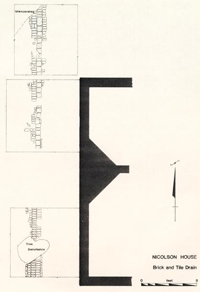

| 15. | Plan of Brick and Tile Drain | 36 |

| 16. | Plan of Fence Lines 1 & 2 | 38 |

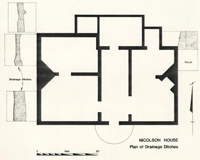

| 17. | Plan of Drainage Ditches | 42 |

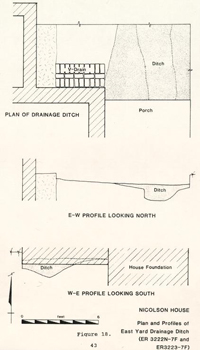

| 18. | Plan and Profile of Eastern Drainage Ditch | 43 |

| 19. | Ceramic Vessels from Eastern Drainage Ditch | 46 |

| 20. | English White Salt Glazed Stoneware | 48 |

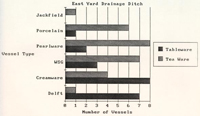

| Table 1. | Ceramic Vessels Located within Eastern Drainage Ditch | 45 |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to many people who provided help and support during the long period which it took to prepare this report. The field crew on this project consisted of Farley Andrews, Virginia Caldwell, Jim Csigas, Roy Jackson, Keith Ogburn, Scott Rhyne, and Nate Smith. Steven Beauter and Sharon Stangroom also helped with excavation. The first phase of this project was supervised by John Hamant. Richard Schreiber and his family were models of patience while their home was literally being dug out from under them. I would like to thank them for their kindness and good spirits throughout the project.

Various members of the Office of Archaeological Excavation staff were involved in this project, from artifact processing through offering advice and support. William Pittman, Laboratory Supervisor, was responsible for the processing of the artifacts, from the washing to the cataloging and crossmending stages. Wright Robinson and Linda Derry assisted in the computer entry of the artifact cataloging. Peter Barlow was responsible for the conservation of artifacts from the Nicolson House excavation. Elizabeth Bush was also an invaluable aid in the artifact processing. Virginia Caldwell and Natalie Larson, draftspersons for the OAE, provided the graphics for the report. Tamera Mams took the artifact photographs and Mike Taylor and Marley R. Brown III were responsible for the field photography. Wynette Gregg was the artifact illustrator.

Other persons within the Foundation were instrumental in this research. Thanks are in order for John Austin, Leslie Grigsby, Mary Keeling, Kim Funke, Mark Wenger, Tom Taylor, Pat Gibbs, Nan Reisweber, and Vernita HoSang. Joanne Bowen Gaynor prepared the faunal report, while Mary Praetzellis of Sonoma State University identified 19th century ceramics recovered during the project.

Final thanks goes to Marley R. Brown, III, who never lost his patience during the years it took to finally complete this report.

CHAPTER 1.

INTRODUCTION

Archaeological investigations were conducted by the Office of Excavation and Conservation of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (CWF) at the Nicolson House from January 7, 1982, until May 20, 1982 (Figure 1). Work was undertaken at this time in order to salvage archaeological evidence adjacent to the house prior to the waterproofing of the below-ground foundation walls. The Nicolson House property is a particularly valuable location for archaeological investigation, since it is one of the few areas in Williamsburg's Historic Area not disturbed by archaeological cross-trenching or earlier archaeological investigations. Unlike most of the properties in Colonial Williamsburg, the Nicolson House was privately owned during the days of the Foundation's intensive and widespread archaeological investigations. When the house was sold to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1964, only minor work was completed in and around the house before turning it into a private residence for employees.

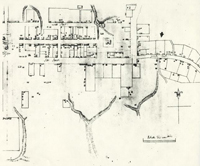

The Nicolson House is shown on the Frenchman's Map of 1782 as having two outbuildings located north and east of the house, none of which have been archaeologically explored (Figures 2 & 3). The property can also be seen on the Desandrouins Map dating to 1782 (Figure 4). The archaeological effort at this time, however, centered on excavation directly around the house, since this was the area to be impacted by the waterproofing activities. The purpose of excavation was not only to remove occupation layers associated with the property, but also to define architectural components contemporary to the building's early years of existence. Since detailed information about the architectural history of the house is scanty, it was also important to trace any changes to the structure that would be discernible through archaeological excavation.

In the front yard, evidence of an early porch structure was sought, as well as fence lines defining property boundaries. Also of particular interest was the testing of the builder's trench for the house, in hope that it would yield artifactual evidence to further corroborate its presumed mid-18th century construction date. Remnants of walkways leading toward the property's outbuildings were expected, as well as traces of repair to the house foundation.

The results of this excavations would in no way present a full picture of the range of activity occurring on the Nicolson House property. At best, the limited scope of this project would provide only a glimpse of the property's history, and that mainly in the form of architectural information about the house. Answers

2

PHOTOGRAPH - Figure 1. Nicolson House, South Façade

3

PHOTOGRAPH - Figure 1. Nicolson House, South Façade

3

MAP - Figure 2. Frenchman's Map, 1781

4

MAP - Figure 2. Frenchman's Map, 1781

4

MAP - Figure 3. Detail of Frenchman's Map Showing Nicolson House

5

MAP - Figure 3. Detail of Frenchman's Map Showing Nicolson House

5

MAP - Figure 4. Desandrouins Map

6

to questions about spatial and behavioral organization on the property are not possible with this type of project.

MAP - Figure 4. Desandrouins Map

6

to questions about spatial and behavioral organization on the property are not possible with this type of project.

Even with this limited range of work, however, it was felt important to use the full range of documentary sources available, in order to paint a full picture of the property's history and place it in the context of 18th century Williamsburg. This report will take an integrated approach to the Nicolson House, combining primary documentary sources, excavated data, and secondary source material (Beaudry 1980) to form an overall view of the site. Various documents and sources were used in researching the history of the Nicolson House and its occupants.

Primary sources included old newspapers, city and county records, merchants' account books, old maps, and photographs. Each of these sources furnished clues in revealing information useful in the interpretation of the site. For example, old maps and photographs detail information on the architectural remains to be examined. Changes in structural appearance (i.e., renovations, additions) are apparent in photographs, while maps indicate the presence and location of buildings and gardens. Fire insurance records are valuable sources of information, particularly concerning building dimensions and property values.

Also, this research relied heavily on legal documents, such as deed books, plat records, and wills, to reconstruct a property title chain. Also useful were documents dealing directly with persons associated with the property. Old diaries, journals, and correspondence are examples of this type of document. In the Nicolson House excavation, a journal kept by James Cogar during the house restoration in 1940 proved to be an invaluable aid in some areas of archaeological work (Cogar n.d.). Other sources of information are found in newspapers and merchants' account books. Through advertisements in the Virginia Gazette, it is known that Robert Nicolson was boarding tenants in his home. Examination of merchants' and craftsmen's account ledgers, such as that of Humphrey Harwood (Harwood n.d.), provided information on the occurrence of structural renovations or the relative social status of the property owner through the types of items which he purchased. Robert Nicolson's purchases of books and prints (Wenger 1982:1-2) imply that he was wealthy enough to afford items which were not considered necessities.

Secondary source materials were also included in this research. Historical and biographical journals are often unexpected sources of valuable information. These journals often publish portions of old diaries, genealogies, and church records, as well as other types of historical data. Prior research on the property had been conducted by Raymond Townsend in the 1960s. Some of the information from his unpublished manuscript on the 7 Nicolson House was used in compiling the house history of this report.

CHAPTER 2.

HOUSE HISTORY

The Nicolson House is located at the east end of York Street, below the Capitol Building, on what had been part of a large tract of land owned by Virginia planter Mann Page. Upon his death in 1730, his son Mann Page II, decided to sell this land in order to settle his father's debts. This property was entailed, however, and it was 1747 before the General Assembly passed an act that allowed its sale. Shortly following this, Page entered into an agreement with Benjamin Waller, whereby Waller would survey the property, divide it into lots, and sell it. This land forming a suburb on the east side of town was surveyed and recorded in the York County records in April of 1749 (YCDB 5: 332-334). Residents of this area, wanting the privileges of property owners in town, petitioned the City of Williamsburg in 1756 for incorporation into the town's limits (Stephenson n.d.), with annexation soon following.

On May 23, 1750, James Spiers, cabinetmaker, purchased Lot 26 for a sum of 10. A clause included in the contract by Waller stated that a dwelling measuring at least 16' x 20' with a brick chimney had to be built on the property within three years. If, at the end of this period, there was no such structure, the lot would revert back to Waller (YCDB 5:363-367). Spiers most likely did not build on the property, for a year later, on May 17, 1751, he sold it to a young tailor named Robert Nicolson. For the same sum of 10, Nicolson bought the two one half acre lots and proceeded to build his home there.

These lots on the outskirts of town, less expensive than those within the city limits, were the setting for a neighborhood of craftsmen and young men just starting their careers. Robert Nicolson was 26 years old when he purchased the lots from Spiers, which would place his birth around 1725. He is not documented as owning any property in Williamsburg prior to this purchase and it is likely that he was just beginning his own tailoring business. Nicolson was married to Mary Waters and at the time of their purchase of Lot 26, they had two children. Together they had seven children in all, five of whom were born while they were living in the house on Francis Street (Goodwin 1941:148, 149, 151). Of their children, Robert, Jr. (b. 1753) became a noted surgeon during the Revolutionary War; George, (b. 1758) became mayor of Richmond, and Thomas, (b. 1757?) became the publisher of the Virginia Gazette and General Advertiser. There were also three other sons, William, (b. 1749), John, (b. 1751), Andrew (b. 1763) and one daughter, Rebecca (b. 1766).

In order to conform to Waller's building clause, Nicolson most likely built his frame house sometime between 1751 and 1753. It 9 was a fairly small, unpretentious two story building, measuring approximately 24' x 26'. It was then similar in plan to the present day reconstruction of the Orrell House, also located in Williamsburg, with a side hall opening onto two ground floor rooms. To help augment his income from the tailoring shop located across the street, Nicolson took in lodgers. That he was boarding lodgers as early as 1755, is documented by this advertisement in the March 28, 1755 edition of the Virginia Gazette:

THE Subscriber, living at Mr. Nicolson's in Williamsburg, proposes to teach Gentlemen and Ladies to play on the Organ, Harpsichord, or Spinett; and to instruct those Gentlemen that play on other Instruments, so as to enable them to play in concert. Upon haveing Encouragement I will fix in any part of the Country.

Cuthbert Ogle

Unfortunately for Ogle, he was dead within a month. Robert Nicolson, his former landlord, became the executor of his estate (Townsend n.d.). Although there is no record of his having boarders in the years immediately following Ogle's death, he most likely was accomodating tenants in his home during the late 1750s and 1760s.

The next reference found to Nicolson's boarding practice is seen when he advertised in the Virginia Gazette of September 12, 1766 for lodgers.

WILLIAMSBURG, SEPTEMBER 12, 1766

GENTLEMEN who attend

the General Courts and Assembly may be accommodated with genteel LODGINGS, have BREAKFAST and good STABLING for their HORSES, by applying to

ROBERT NICOLSON

The cost of "Bed and Breakfast" was 3 a month. It is likely by the time of this advertisement that the western addition had been built onto the house. With five children between the ages of a newborn and fifteen, Robert Nicolson and his wife would have hardly been prepared to house the family and lodgers in the original house. The addition of two bays on the western end of the structure doubled its size, giving the house its present dimensions of 28' NS x 46' EW. The double pile central passage 10 structure has remained virtually unchanged since the eighteenth century, with only the east side and back subsequently altered by porch additions. The account book of Humphrey Harwood, a Williamsburg carpenter, for the period 1786-1794 showed that he made some repairs and built additions to Nicolson's house and shop. The plan of the construction sequence of the Nicolson House has been prepared by the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Architectural Research (Figure 5).

Like most landlords, Nicolson endured his share of troubles with tenants. A highly publicized disagreement between boarder James Mercer, a Burgess for the County of Hampshire, and Dr. Lee, a Williamsburg resident, took place in 1767. This dispute almost ended in a duel, and various accounts of the episode were detailed in the Virginia Gazette following the incident. This trouble obviously did not deter Mercer from boarding at Nicolson's, as seen in the Virginia Gazette of November 4, 1773:

Williamsburg, November 4, 1773

I SHALL return here the 20th instant: In the interim, Mr. Robert Nicolson will receive any payments that any person may incline to make him for

JAMES MERCER

Nicolson, having finally tired of the annoyance of paying tenants, or reaching a point where it was no longer a financial necessity, announced his decision to stop taking in boarders in 1777:

WILLIAMSBURG, April 11, 1777

THE Subscriber begs Leave to inform Gentlemen who for these several Years past used to put up at his House, that he has now entirely discontinued taking in lodgers.

ROBERT NICOLSON

(Dixon and Hunter, 1777)

In 1773, Robert Nicolson moved his business into the center of town, buying a shop on Duke of Gloucester Street. Besides tailoring services, Nicolson's shop served as a subsidiary post office and a general store. His son, William, set up business in his father's old shop across from the Nicolson House.

11 FLOOR PLAN - Figure 5. Construction Sequence of Nicolson House

FLOOR PLAN - Figure 5. Construction Sequence of Nicolson House

Robert Nicolson's prestige within the community seems to have grown along with his business. In December, 1774, he was appointed to serve on a pre-Revolutionary citizens committee which included, among others, Peyton Randolph, George Wythe, and Thomas Everard (Anonymous 1896: 250). During the Revolutionary War, Nicolson employed soldiers in his shop to make uniforms for the state (PSW 1778).

Nicolson continued to purchase land throughout the last half of the 18th century; and the tax books of 1797 show Nicolson as owning 135 ½ acres of land (YCTB 1797). In 1783, Nicolson owned one free male, five adult slaves, and seven slaves under the age of sixteen (Anonymous 1914:138). This compares with other Williamsburg notables, such as George Wythe, shown in the same tax list as having fourteen slaves, and Benjamin Waller, with thirteen. Nicolson also owned two horses, two cows, and a two wheeled vehicle called a chair.

Apparently, Nicolson resided in the house on "Woodpecker Street" for the remainder of his life. Fire insurance records of 1796 state

"I . . . Robert Nicolson residing at Williamsburg . . . declare for assurance . . . against fire on Buildings . . . My wooden Buildings on Woodpecker Street at Williamsburg now occupied by myself situated between the lott of Saml Goodson and that of Mrs. Craig . . ." (MAS 112).

When Robert Nicolson died in 1797, his estate passed into the hands of his surviving children. In the following year Dr. Robert Nicolson, Jr. died, but the property remained in the Nicolson estate until it was sold to John Power in 1803 (WLT 40:4). John Power died soon thereafter, leaving the property to his son, John Power, Jr. When the son was killed in the Battle of Hampton on June 25, 1813 (Flournoy 1968:256), the property remained solely in the hands of John Power's other children.

The house remained within the Power family, with the next recorded mention of the property not coming until 1841. In that year, James T. Bowery claimed to have agreed with Allan and Ann Chapman and other heirs of the Power estate, upon a thirteen year lease to the house. Effective January 1, 1841, Bowery would rent the house on Woodpecker Street for the sum of $100 a year. However, on January 2, 1841, Allan Chapman and Richard Roe forcibly evicted Bowery from the property, using "staves, sticks, and knives" (Southall). No reason was given for the cause of the eviction. Bowery filed suit against the Chapmans for damages; in retaliation, the Chapmans filed a countersuit to remove Bowery 13 from the property. John Power's heirs eventually won their suit and Bowery was forced to vacate the property.

In 1846, John Slaughter made a down payment on the York Street property. Until his final payment in 1851, the property continued to be taxed to the Power estate (WLT 40:14). Slaughter had apparently lived in the house since the time of his purchase, but in 1854 decided to sell or rent the property. He placed the following advertisement in the Virginia Gazette (January 5, 1854):

"The undersigned being desirous of removing to the country offers for sale or for rent the ensuing year, two houses and lots located on Woodpecker Street. One is a new house recently finished, suitable for a small family, there being a large room and a passage below and two comfortable rooms above. The other in which he now resides is a large and commodious building containing ten rooms all in thorough repair. Both of these dwellings have good lots and all the necessary outhouse attached to render them comfortable. There is a well of good water in the yard convenient to both dwellings.

The location is but short distance from the Female Academy, now in a flourishing condition, and the larger dwelling is admirably suited for a boarding house.

There is a storehouse located between the above described dwellings which the subscriber will either sell or rent.

For terms, apply to him in the city of Williamsburg.

JOHN SLAUGHTER

Slaughter must have rented the house almost immediately, since the following announcement appeared in the January 26, 1854 edition of the Virginia Gazette:

Attention!!

William Lindsey would respectfully announce to CARPENTERS and BUILDERS of Williamsburg and surrounding country, that he has opened a SASH, BLIND, and DOOR MANUFACTORY, about THE CENTRE OF "WOODPECKER" STREET, in the house formerly occupied by Mr. John Slaughter, where he will 14 be prepared to carry on the above business in all its branches. All orders received by him will be promptly attended to and neatly executed.

The smaller dwelling became Abraham Hoffheimer and Brothers grocery and dry goods store (Martin 1854).

No records exist for the Nicolson House property during the Civil War period. Many houses on York Street were vacated during the three year Union occupation of the town, and consequently fell into disrepair or were damaged by marauding soldiers. For example, Isaac Smith and his wife, who rented the property immediately west of the Nicolson House, repaired damages to that house in lieu of paying rent. In 1865, the Nicolson buildings were valued at a sum of $1700, (a depreciation of $700 from the year 1854), so it seems very likely that the property suffered during the Civil War.

The last quarter of the 19th century was witness to a lengthy and complicated court battle involving the Nicolson House. For some time, John Slaughter had been experiencing financial difficulties which he was not able to alleviate. To ease his monetary problems, he was granted a stay of execution by the court that allowed him to postpone payment of his debts. Before this stay expired, in December of 1868, he deeded his house and property to Robert H. Armistead as trustee to secure a bond to Lavinia E. Lawson. The bond was for a debt of $800 plus interest from March 1858 owed to Lawson, and for liabilities to other individuals incurred by Slaughter. Meanwhile, in 1867, William Lively brought a suit against Slaughter for an uncollected debt owed to Charles Lively since July, 1849. The court ordered Slaughter to pay the debt, with interest, but no settlement was made.

Slaughter died in intestate in 1869 or 1870, and following the death of Slaughter's widow around 1873, Armistead sold the Nicolson House and property to Lavinia Lawson. William Lively then complained Lawson had not paid the full value for the property, and that for the restitution of his debt, the property should be resold. Lawson, who had settled some of Slaughter's other debts, resigned her claims to the property. Lively versus Slaughter went to court in 1877; and consequently, when Slaughter's estate was evaluated, it was found to be worth less than his accrued debts. It was ordered that the house be sold at public auction by Armistead and R. L. Henley to defray court costs and the debts (CW/CJCCOB 2:284). After a five year delay by Armistead and Henley, the property was sold in 1883 by Court appointed commissioner H. B. Warren to John W. Lawson (CW/JCCCH 64). Lawson was granted a special warranty deed to the property on September 16, 1885.

15In 1894, John Lawson sold the Nicolson property to Bascom Dey, who already owned the lot to the east of the house (CWDB 2:595-596). Sometime prior to 1923, Dey died and his widow sold the property to Luther Lindsley and his wife Pattie Love Jones Lindsley (CWDB 10:65). Pattie Lindsley died before her spouse, leaving her share of the property to her mother, Pattie Bugg Jones, who later deeded it to Luther Lindsley.

In August, 1940, James L. Cogar purchased the Nicolson House property from Lindsley (CWDB 18:319-20). Photographs taken of the house around the time of Cogar's purchase show it to be dilapidated and overgrown with vines (Figure 6). He soon thereafter began to restore the house to its 18th-century appearance, with his goal to make the house livable while changing as little as possible of the original structure. Progress was charted through a diary that Cogar kept during the renovation.

Cogar lived in the house until 1964, when he sold the property to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (CWDB 36:311-312). It is now serving as housing for company employees, and is presently the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Richard Schreiber. Mr. Schreiber is the Vice President of Products Division.

16CHAPTER 3.

FIELD METHODS AND ANALYSIS

Archaeological work began on January 7, 1982 with an excavation crew led by John Hamant of the Office of Excavation and Conservation. On March 10, a crew of three additional excavators began work in the front yard of the house. Since the only area to be impacted by the waterproofing was directly adjacent to the house, the work plan was comprised of placing excavation units abutting the foundation walls. Excavation was to be conducted along every side of the building, except the east, which had been disturbed by the installation of an oil tank. No base line was established; instead, excavation units were measured directly off of the house foundation. These units extended a distance of ten feet out from the foundation on the south, north and west sides of the house. In the backyard, however, to the east of the existing bulkhead entrance, excavation was only extended six feet from the foundation. The placement of these units and their square designations are shown in Figure 7.

Because of time limitations due to the Maintenance Department's waterproofing schedule, the uppermost layers of fill were shovel-shaved. While shoveling, excavators watched for the appearance of archaeological features cutting through the soil strata. The fill of all such features was removed with trowels. Below the twentieth century strata, the soil was excavated using trowels. Layer changes were determined by color and/or texture changes in the soil, and those which appeared to be undisturbed 18th-century fill were screened through ¼" wire mesh. Features were mapped in plan and profile, sectioned, and photographed. Excavation continued until sterile subsoil was reached in all areas. To insure the least possible amount of water damage to the house during the excavation, all above ground gutters were the last areas to be excavated. The strata under these drains were assigned separate provenience numbers.

Recording of data took the form of descriptive notes on each layer and feature, with each layer having been assigned a unique numerical designation. These excavation register numbers were composed of a number which stood for the excavation unit in question, followed by a letter designation for the feature or layer. If, for example, the topsoil was the first strata removed from the excavation unit ER3212, then it would be designated as ER3212A. The next layer removed would be ER3212B, and so on. Features, such as post-holes or trash pits, were also assigned letter designations. If the number of soil layers and features in a particular unit exceeded twenty-six, then a new second number would be assigned to the excavation unit and the process would continue, beginning with Layer or Feature A.

18CHAPTER 4.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESULTS

Excavation revealed that the areas examined along the west and north facades of the house had been heavily disturbed through a variety of activities. Numerous utility trenches criss-crossed the area, and interpretation was hampered by quantities of redeposited fill and extensive root disturbance, particularly on the west side of the house.

Unlike other properties in Colonial Williamsburg, where extensive excavations have taken place (the Peyton Randolph backyard, Shield's Tavern), consistent soil layers with sheet refuse were not located at the Nicolson House. This was due to the limited size of the excavation and the amount of disturbance that had occurred around the house. This limited scope made it difficult to make statements about patterns of activity occurring around the house. Information from the archaeological excavation has been grouped for the purposes of this report into the following three categories: house-related architectural features, like builder's trenches and renovation episodes, other landscape features, such as fence lines and walkways; and miscellaneous features. Each category will be discussed in this chapter.

A. Nicolson House Architectural Features

Builder's Trench

(Feature 1)

One of the objectives of the excavation around the foundation was to see if artifacts contained within the builder's trench of the house would aid in dating its original construction, as well as that of the addition. Since the Nicolson House contains a full cellar, however, it was not expected that a builder's trench would be present along the outside foundation walls. Generally, workers standing inside the newly excavated cellar would construct the building foundation by laying the brick up against the perimeter of the cellar hole (Noël Hume 1975:118). Often, however, the excavated cellar holes would be slightly larger than the intended foundation, thus leaving a narrow trench encircling the outside of the structure's walls.

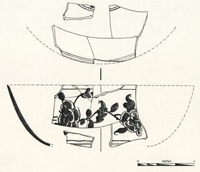

A narrow builder's trench (1.0' wide), abutting the foundation walls, was located along the north and south facades of the Nicolson House. Although time did not permit a complete excavation of the trench, both areas were tested by removing sections of the fill. This fill was composed of redeposited yellow clay subsoil, most likely generated by the excavation of the cellar. Fragments of a blue and white delftware punch bowl (Figure 8) dating between 1740 and 1750 (John Austin, personal communication) were found in this trench and corroborate the expected construction date of the house. The remaining artifacts, consisting of nails and window glass, were less closely datable than ceramics and likely related to construction activities. The trench, filled after the foundation walls were completes, would have been a convenient place to dispose of garbage generated on the construction site, such as bent nails, broken glass or food scraps. In an area which had not been previously occupied, such as this, it would not be expected that there would be a great deal of refuse scattered on the lot that would find its ways into the builder's trench, so most of the material in the trench would be related to the house construction.

On the south and north sides of the house, repair to the brick foundation cut the original builder's trench to a depth of 2' below the present ground level. Remnants of plaster or mortar smeared over the face of some of the below-ground brick indicate this as an attempt to halt water leakage into the basement. Inclusions of porcellaneous bodied ceramics and white ware date this repair to post 1820 (Pittman 1984). Excavation beneath the front steps revealed that they were not removed for this

21

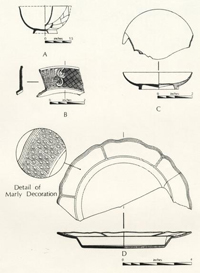

ILLUSTRATION - Figure 8. Delftware Punch Bowl from Builder's Trench

22

foundation repair, with the narrow 18th-century builder's trench remaining intact.

ILLUSTRATION - Figure 8. Delftware Punch Bowl from Builder's Trench

22

foundation repair, with the narrow 18th-century builder's trench remaining intact.

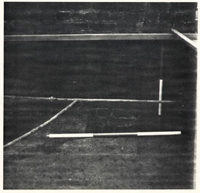

A narrow builder's trench was partially excavated along the foundation of the western addition. Artifacts dating from the early 19th century were included in this fill and appear to relate to repair work done on the foundation walls in the 19th century. Examination of the below-ground brick foundations in the northwest corner show a large area where the brick are not joined with mortar (Figure 9). Bricks jutting out from the face of the foundation wall appear to have been shoved in with an attempt at a repair.

Front Porch Structural Remains and Walkway

(Feature 2)

One of the objectives of the front yard excavation was to determine if any traces remained of the original front porch for the house. Before the addition of the two western bays around 1766, the front door was located at the west end of the building. If the semi-circular stone steps now serving the front door had been in place since the original construction, then they would have extended beyond the original foundation of the house. Although it is obvious these steps are not original to the c. 1751-53 house construction period, there is no documentation of when these steps were added. Their installation probably dates to the construction of the west addition, and definitely prior to a 19th-century repair to the south foundation.

Since excavation on either side of the steps revealed no evidence of a porch structure, the stone steps were removed in order to allow excavation beneath them. A line of brick (Feature 2) located directly below the steps was mapped and photographed in the event it was a remnant of an earlier porch structure. After excavation, however, it was apparent that these brick served as seating for the stone steps. During, the 1940s restoration, the steps were removed and the abutting foundation wall pointed with mortar (Cogar n.d.), so the brick-seating could date either to this time, or to the period of the steps' original installation. Since the bricks match that of the first period house foundation in color and size, this would seem to indicate the stone steps were added when the second period addition was constructed. Brick removed from the first period foundation were then available and handy to use as seating for the steps. All artifacts removed from the area beneath the steps dated to the 18th century, further substantiating this conclusion.

23 PHOTOGRAPH - Figure 9. Northwest Foundation Wall Showing Repair

PHOTOGRAPH - Figure 9. Northwest Foundation Wall Showing Repair

When the stone steps were first installed, the surrounding ground was most likely cut or graded in order to seat the stone. This grading, however, would have been unlikely to have destroyed all remnants of a post construction porch. Traces of the post-holes and postmolds related to the porch should have been evident cutting subsoil. Thus, it does not appear likely that the original entrance into the Nicolson House was a substantial post-supported porch.

Since no conclusive evidence for a porch structure was located through archaeological techniques, two other possibilities for the design of the original porch are proposed. The original front porch of the house may have been similar to those present on the Orrell House and William Randolph Lodgings, also located in Colonial Williamsburg. These consisted of a small wooden porch and stairs supported by an insubstantial brick foundation (Figure 10a). With the brick not set deeply below ground level, this type of porch could have easily disappeared without leaving archaeological traces. It should also be noted that the Orrell House, an original 18th-century dwelling, is structurally very similar to the Nicolson House prior to the construction of its western addition.

Another possibility, although less permanent in nature, is the type of entrance seen on various structures in the historic district, including the Alexander Craig House and the William Randolph Lodgings. At these dwellings, wooden steps lead directly up to the door, with no porch landing (Figure 10b).

A series of small round features were revealed after the removal of the steps, approximately 3" above sterile subsoil (Figure 11). Since the size, depth and fill of these features were very similar, it is speculated that these holes were related and may have been part of the original porch structure. Unfortunately, no artifacts were recovered from any of the features that provided any indication of their dating.

Located opposite the front door was a strip of crushed orange brick rubble. This walkway began approximately five feet from the south foundation wall and ran south toward the street. No artifacts were contained within the brick to date the its deposition, but the rubble ran underneath the stone steps, thus predating their installation and associating this walkway with the earliest period of the house occupation.

25 Possible Front Porch Reconstructions for Nicolson House

Possible Front Porch Reconstructions for Nicolson House

DIAGRAM - Figure 11. Plan of Postholes under Front Stone Steps

DIAGRAM - Figure 11. Plan of Postholes under Front Stone Steps

Back Porch Structural Remains

(Features 3 - 6)

Prior to the beginning of the excavation, the flooring of the modern back porch was removed and the fill below the porch and adjoining crawl space was excavated. The foundation walls of the porch and crawl space were used as boundaries for the excavation units (Figure 7). In addition to the examination of these areas, a 10' X 10' unit was also placed on the northwestern corner of the house. Excavation was taken to sterile subsoil, except under the crawl space, where work was halted for fear of damaging the structural integrity of the building. Excavation revealed evidence of several back porch structures (Figure 12). Each of these porch structures will be discussed below.

Located under the present porch were the remnants of a brick wall and a step support (Feature 3). This brick work can be seen as the back porch in a 1933 photograph of the house (Figure 13). These bricks, dark red in color, were bonded with tan, heavily shelled mortar.

Below the remains of the porch seen in the 1933 photograph was a brickbat walkway (Feature 4) leading from the back door and running along the back of the house to the west. Directly beneath the current (and original) back doorway of the house was a semi-circular area which was free from brick rubble (Figure 12b). This brick-free area appears to have been the location of stone steps similar to those now present on the front of the house. If the conjectured semi-circular steps were associated with the brick walkway, as the stratigraphic evidence appears to suggest, then artifacts recovered within the brick walk would aid in dating the period when the steps were in use. Along with ceramics typical of the mid-18th century, such as Jackfield, Nottingham stoneware, and lead glazed slipware, was a piece of polychrome pearlware, whose inclusion suggests, the sidewalk was in use as late as 1795 (Noël Hume 1969:129). Beneath the rubble walkway was an area of crushed and burned shell (Feature 5) which represented an earlier walk. There were no artifacts found in association with this walkway.

Beneath the remnants of the brick rubble and shell walkways, a thick layer of redeposited clay sealed the remnants of yet another doorstep. This clay deposit contained fragments of the delftware bowl found in the builder's trench, giving the redeposited clay a terminus post quem of 1740-1750.

The earliest porch feature consisted of a shallow trench running parallel to the north wall of the house at a distance of two feet from the foundation (Feature 6). Three brick supports

28

Figure 12. - Three Periods of Back Porch Construction

29

Figure 12. - Three Periods of Back Porch Construction

29

PHOTOGRAPH - Figure 13. Nicolson House, North Façade 1933

30

(with a fourth probably later destroyed by a more modern feature) were contained within the trench fill and spaced two feet apart. Each consisted of two brick, stacked one upon another and not mortared. Since the brick are the same color and size as those in the house foundation, it is postulated that these date to the construction of the house and originally served as step supports (Figure 12c). The earliest porch structure sealed a strata of dark grey loam with brick fragments and a spread of heavily shelled mortar (ER3203B). This layer, whose artifacts dated to the 18th century, is probably associated with the first period of construction.

PHOTOGRAPH - Figure 13. Nicolson House, North Façade 1933

30

(with a fourth probably later destroyed by a more modern feature) were contained within the trench fill and spaced two feet apart. Each consisted of two brick, stacked one upon another and not mortared. Since the brick are the same color and size as those in the house foundation, it is postulated that these date to the construction of the house and originally served as step supports (Figure 12c). The earliest porch structure sealed a strata of dark grey loam with brick fragments and a spread of heavily shelled mortar (ER3203B). This layer, whose artifacts dated to the 18th century, is probably associated with the first period of construction.

Bulkhead Entrance

(Feature 7)

Excavation along the western end of the north foundation wall revealed a backfilled bulkhead entrance into the cellar of the house. All that remained of the original entrance was the bottom brick step and a portion of the step above it (Figure 14). No documentary records exist which date the construction or destruction of the bulkhead entrance. Artifacts found between the bricks of the bottom step date to the colonial period, suggesting that the bulkhead was original to the western bay addition.

The foundation wall adjacent to the step, where the doorway to the cellar had been previously located was very poorly constructed, with large amounts of mortar oozing out from between the bricks and smeared over the face of the wall. Since the brick used to patch the wall were the same color and size as that of the remaining step, it appears that brick from the bulkhead construction were used to seal the doorway.

Although there were several distinct tips of soil within the bulkhead fill (Feature 7), the deposition of these layers probably occurred simultaneously. A wide range of 18th & 19th-century ceramics was represented in the fill, with crossmends between this strata and a 20th-century fill layer dating the sealing of the bulkhead to this century, perhaps to the Bascom Dey occupation of the property.

31 Figure 14. Plan of Bulkhead Entrance and Outbuilding Remains

Figure 14. Plan of Bulkhead Entrance and Outbuilding Remains

Renovation Debris

(Features 8 & 9)

Approximately one foot below present grade, in the front yard, a spread of brick and shell mortar rubble was exposed (Feature 8). The brick rubble is of the same color and type as that used in the first period construction of the house. Ceramics associated with this layer, which included sponged white ware, Canton porcelain, and hand painted pearlware, date the deposit after 1820 (South 1977:211). Most likely, this rubble was generated in association with repair work done to the house foundation during the first half of the 19th century. Examination of the east side cellar windows show some patching has been done around them; however, no records have been located to indicate when this occurred. The rubble may have been associated with this repair.

In the backyard, the first undisturbed stratigraphic layer composed of shell mortar and plaster fragments, was located directly behind the house (Feature 9). This layer ranged from 1" to 7" in depth, being its thickest against the foundation wall of the house. The layer became gradually thinner as it spread to the north and west until it ended as a lense approximately 5' from the house. Sherds of hand painted polychrome and annular banded white ware date the deposition of this debris after 1830, indicating that some interior remodeling of the house occurred after the first quarter of the 19th century. Judging from the area covered by the mortar spread, it appears that workmen dumped the broken plaster from the back window located just above the bulkhead entrance. Both of these renovation episodes may have occurred when John Slaughter purchased the house in 1846.

Possible Shed or Fence

(Feature 10)

Also located in the back yard were two post-holes, running in a north/south direction off the northeast corner of the house. Ceramics from these holes date to the late 18th to early 19th century, and may represent a fence line or shed structure extending from the back of the house.

Outbuilding

(Feature 11)

Located to the northwest of the brick and tile drain were the brick foundations of an outbuilding (Figure 14). The south half of the mortared brick foundation had been destroyed by a pipe trench and repairs to the house foundation, while some of the bricks to the north had been robbed. The foundation measured 7' from east to west, but the disturbances to the south made determination of its full dimensions impossible. Composed of orange and salmon brick bonded with shell mortar, the foundation was only two courses deep, consistent with frame constructed outbuildings set on shallow brick underpinnings. Remnants of a brick bat floor were evident within the foundation walls. Dating evidence from layers and features found in association with the outbuilding indicates that the building was in use during the second quarter of the 19th century. The brick foundation and the brickbat floor were constructed over a layer (ER3208N) deposited after 1830, giving a terminal date for construction. Artifacts from the soil strata (ER3208E, ER3204X) overlying the brick foundation indicate that the building was destroyed sometime after 1850.

The function of structures "is not an interpretation easily arrived at by the archaeologist" (South 1977:232), even when the structures did not usually reflect the documented function. The artifact assemblage from the Nicolson outbuilding (which included fine tablewares, coarse storage vessels, and nails) did not provide any definitive clues as to the structure's function. However, through examining architectural details, certain functions for the structure can be eliminated. Privies and smokehouses can be ruled out this way. The main feature of a privy; a deep pit for the containment of refuse, was not present in the structure. Smokehouses, as a rule, have dirt floors, while this outbuilding had a brick bat floor.

The possibility of a dairy cannot be ruled out in this manner, however. Sally A. Smith has stated in her thesis on Chesapeake dairies that the most frequent dairy dimensions in the 18th century were 12' x 12' (1982:21). This is substantially larger than the Nicolson outbuilding. However, written records show that the Archibald Blair dairy (in Colonial Williamsburg), measured 9'3" x 9'0" (Smith 1982:21). Keeping in mind that the north/south dimensions are unknown, it would be possible for a dairy to be as small as the outbuilding located at the Nicolson House. According to Smith (1982:44), most dairies are located close to the dwelling, at the side or the rear. The Nicolson outbuilding was located within 2' of the backfilled bulkhead 34 entrance and less than 5' from the north foundation wall of the house.

B. Landscape Features

Brick and Tile Drain

(Feature 12)

A drain constructed of brick and tile was located running parallel to the west wall of the house (Figure 15). The bottom of this open drain was composed of light salmon colored brick tiles measuring 8" x 8" x 2 ¾". The drain's sloping sides were constructed of brick (8" x 4" x 2"), varying in color from a medium to a dark orange. In unit ER3210-7F, regular brick was placed along the bottom of the drain, perhaps indicating that there were not enough tile to complete the construction of the drain. In one instance, (ER 3208-7F), a large flat stone replaced the tile.

The composition of the layer sealing the drain and the fill of the drain itself were indistinguishable and were removed as one context. This layer, ranging from 6"-8" thick, consisted of a brown, spongy loam containing brick bits, shell and sand mortar bits, ash, and oyster shell (Feature 13). A wide variety of ceramics were recovered from this deposit, ranging from those popular in the mid-18th century, such as English white salt glazed stoneware and cream-ware, to metals and plastics manufactured in the 20th century. It is hypothesized that this fill was brought in during the 1940s restoration of the house by James Cogar. The origin of this fill is not known; however, interviews conducted by Andrea Foster with former Colonial Williamsburg archaeologist James M. Knight, revealed that spoil dirt from archaeological excavations within the historic area was often removed to be used as topsoil in other locations (Knight, personal communication December 9, 1982). since the artifacts from this layer have been removed from their primary context, they do not relate to activity at the Nicolson House.

The consistent appearance of the soil throughout this thick layer, the wide date range portrayed by the ceramic assemblage, and the lack of crossmends with other areas of the site supports the hypothesis that this layer represents redeposited soil brought in as fill, perhaps for a garden. No evidence of silting was found in the bottom of the drain, which appears to have remained open until the deposition of the fill layer.

The drain cut a layer of soil whose ceramic assemblage included a flow blue teacup. This cup was decorated in the "Kin Shan" pattern, which was being produced by Edward Challinor (Blake 1971:Plate 7) sometime between c. 1842 and 1867

Working Files 0228 add

36

Figure 15. Plan of Brick and Tile Drain

37

(Godden 1971:61). Although there were no maker's marks evident on the recovered sherd, it is probably safe to assume that the construction of the drain post dates 1842.

Figure 15. Plan of Brick and Tile Drain

37

(Godden 1971:61). Although there were no maker's marks evident on the recovered sherd, it is probably safe to assume that the construction of the drain post dates 1842.

From the evidence recovered therefore, it seems that the drain was constructed sometime after 1842, remaining open and in use until being sealed with the loamy redeposited fill. Inclusions of 20th century artifacts, such as aluminum strips, a .22 caliber cartridge case, a Dupont paint tag, and a bakelite comb date the deposition of this layer as occurring in the 20th century. A terminus post quem of 1909 is provided by a bakelite comb (Burchfield 1972:186).

The drain, located 6' from the west side of the house, sloped downhill slightly from north to south as it continued out toward York Street. The Nicolson House has a gambrel roof, allowing rain water to be shed off of the front and back of the building into V-shaped drains abutting the house. This, along with the fact that the drain does not make a 90 turn east toward the structure, makes it seems safe to assume the drain did not serve the house. More likely, it served an outbuilding, such as a kitchen or dairy. Information derived from speaking with members of the Colonial Williamsburg Construction and Maintenance Crew indicated that an old well, capped approximately twenty years ago, was located approximately 20' north of the limits of ER 3208-7F. Possibly, a brick apron surrounded this well and spillage was carried away from that area by the drain.

Fence Lines

(Features 14 & 15)

There were several fence lines present at the Nicolson House. These will be discussed in terms of dating, location, and spatial boundaries within the property.

Fence Line 1 (Feature 14)

A series of nine small post-holes delineating a fence line cut the brick and tile drain (Figure 16). Running parallel to the west side of the house, the holes were similar in size, depth, and fill, and were spaced at approximately 2' intervals. The probable location of four other holes within unexcavated areas between units are also shown in Figure 16. The line of holes between units are also shown in Figure 16. The line of holes extends north-south and makes one ninety degree turn west at the southwest corner of the house, indicating the fence had enclosed the area between the Nicolson House and the Cogar Shop. Although the other 90 degree turn at the northern extent of the fence was

38

Figure 16. Plan of Fence Lines 1 and 2.

39

not located, it is believed that it had been located directly west of ER3208R, since no holes were found extending north beyond it. Large roots in the northwest corner of the square prevented this area from being examined. This fence was most likely built in connection with the fill dirt deposited in this area in the early 20th century. Several of the holes cut the brick and tile drain, and in one instance, bricks from the drain were found in the posthole fill, wedged against the darker soil stain of the postmold. These brick were obviously used as further support around the wooden post.

Figure 16. Plan of Fence Lines 1 and 2.

39

not located, it is believed that it had been located directly west of ER3208R, since no holes were found extending north beyond it. Large roots in the northwest corner of the square prevented this area from being examined. This fence was most likely built in connection with the fill dirt deposited in this area in the early 20th century. Several of the holes cut the brick and tile drain, and in one instance, bricks from the drain were found in the posthole fill, wedged against the darker soil stain of the postmold. These brick were obviously used as further support around the wooden post.

A terminus post quem of 1909 for the redeposited fill was derived by the inclusion of a bakelite comb (Burchfield 1972:186). Since the post-holes cut the fill lay the fence construction had to postdate 1909. Examination of photographs from circa 1928-1933 (Colonial Williamsburg Architectural Research Library) does not show a fenced area to the west of the house. They show instead a line of shrubbery running east/west between the Nicolson House and the Cogar Shop. The fence, apparently then, would have been in existence sometime between 1909 and 1928, during the time that Bascom Dey owned the property.

Fence Line 2 (Feature 15)

Various legislative acts concerning fences are found in local 18th-century records. An act concerning lots on Duke of Gloucester Street was passed in 1705. This act stated "that every Person having any Lotts on half Acres of Land contiguous to ye great Street shall inclose ye said Lotts or half acres with a Will Pales or Post and Rails within six Months after ye Building which ye Law requires to be erected" (Goodwin 1940:347-348). Although such fencing was not required for structures along the side streets of Williamsburg, it would not be uncommon for such fence lines to be used to denote property boundaries.

A second fence line was also located running north/south along the west side of the house (Figure 16). The post-holes were spaced with 8' centers. It is postulated that the fence turns a 90° angle and enclosed the front yard at a distance of 5' from the foundation, since several more post-holes were located running east-west south of the house. Fragments of underglaze blue and white Chinese porcelain were the only form of ceramic found within the fill of the lien of post-holes. The difficulty of dating Chinese porcelain makes establishing a close terminus post quem on the construction of this fence lien difficult, but the ceramics are similar to types known to have been produced in the 18th century.

The fence line was apparently part of a long term property boundary, since five of the seven holes showed signs of later 40 repair or post replacement. Artifacts from several of the repair holes, dated to post 1785, indicating a date after which the repairs occurred. Since there were no artifacts in any of the repair holes, whose terminus post quem was later than 1785, it seems reasonable to assume that the original post-holes (fence-line) was constructed somewhat earlier, probably to the first period of house construction.

Spacing the post-holes 8' apart would place two more holes right at the front door of the house, leaving enough space between them (approximately 5') for a gate. This area was not excavated, so the remains of these post-holes should be present under the current slate walkway.

Documentary records exist for fences similar to this one. In 1722, church wardens of the Bristol Parish were ordered to "take care and rail in the Chappell and the church five rails in one pannell four foot and half high and eight foot in length" (Chamberlayne 1898). Also, in 1774, the Truro Parish ordered that the churchyard was to be enclosed with

"a Post and Rail Fence in the following Manner, to wit, with Sawed Cedar Posts to go two feet and a half in the Ground, to be first burnt, Sawed Yellow Pine Rails clear of sap, five feet high from the surface to the top Rail, Post eight feet asunder, the whole to be well payed with turpentine and red paint" (Truro Parish 1974:135-136).

From these two examples and examination of other contemporary documents, it appears that a fence whose posts were spaced with 8' centers were consistently 4' to 5' tall. The post-holes for the Nicolson fence were about 2' deep, not set quite as deeply as in the instructions given above, suggesting perhaps that it was not quite as substantial as those specified in the 18th century records. One post repair (ER 3212C/D-7F) still contained remnants of a wooden post which was identified as eastern yellow pine. No evidence was found of this post having been burnt, as per the instructions given the Truro Parish. Burning the post's would prevent it rotting as rapidly in the ground as one which remained untreated.

Figure 16 shows placement of the fence line and postulated gate in relation to the present house. From this it can be seen that the stone steps and gate could not co-exist. Since it appears likely that the steps were set in place at the time of the western addition (c. 1766), it is most probable that the fence was erected at the time of the initial house construction. The crushed brick sidewalk discussed previously probably dates to the same period as the fence line. Excavation to the east of the house should reveal the fence line continuing to the edge of Nicolson's lot.

Drainage Ditch

(Feature 16)

Present and cutting sterile subsoil on both the east and the west sides of the house were narrow ditch-like depressions. These ditches were oriented in a north/south direction, continuing past the limits of excavation in both areas (Figure 17). Each sloped slightly downhill to the south, and on the east approximately 1' below the top of the features (Figure 18). The feature on the west side had apparently been cut by the 19th-century brick and tile drain, which may account for its relative shallowness (2-7") in comparison with the eastern ditch. The ditch's fill consisted of a grey ashy silt and on the east side of the house contained enormous quantities (4,272 fragments) of wine bottle glass, plus other domestic refuse.

Although these depressions may represent construction related features, such as trenches for setting brick V-drains, the slope and unevenness of the sides indicate that the trenches remained open and were eroded. Some silting was apparent in the bottoms of the trenches, which were apparently filled with domestic trash towards the end of the 18th century. These features appeared to post-date the c. 1766 addition, since the bottom of the trenches were equidistant from the east and west foundation walls, at a distance of approximately four feet. Further testing to the north of the areas excavated would be warranted to discover the boundaries and function of these features. If they were, in fact, drainage ditches, as they appear to be, perhaps they were serving outbuildings in the backyard.

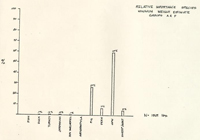

Due to the abundance of cultural materials from the east yard drainage ditch, this feature was chosen for analysis. Ceramics, most often used as the primary dating indicator of an archaeological deposit, were present in a substantial quantity (N=618). They represented a range in manufacture date from the mid-to late 18th century. Underglaze blue transfer printed and hand painted pearlware were the most recent ceramics within the assemblage, placing the filling of the ditch after 1795 (Noël Hume 1969:128).

The fill appears to consist of secondary refuse, defined here as objects discarded at a place different from their location of use (Schiffer 1972:161). The ceramics from the ditch are of many diverse types, very fragmentary in nature, and each vessel was represented by only one or two fragments. These characteristics are consistent with those of secondary fill (Wise 1976). The ceramic assemblage seems to typify what South labels "adjacent

42 Figure 17. Plan of Drainage Ditches

43

Figure 17. Plan of Drainage Ditches

43 Figure 18. Plan and Profiles of East Yard Drainage Ditch (ER 3222N-7F and ER3223-7F)

44

secondary refuse" (1977:48), which accumulates in yards and is dispersed through a variety of human, animal and environmental activities. Concentrations of such refuse accumulate near doorways and in low-lying areas, such as the ditch.

Figure 18. Plan and Profiles of East Yard Drainage Ditch (ER 3222N-7F and ER3223-7F)

44

secondary refuse" (1977:48), which accumulates in yards and is dispersed through a variety of human, animal and environmental activities. Concentrations of such refuse accumulate near doorways and in low-lying areas, such as the ditch.

Examination of the characteristics of the ditch artifacts reveal insights into the purpose of the ditch. A wide date range of 18th century ceramics were represented in the fill of the non-reconstructable, represented in each case by only several sherds.

There is little doubt that these artifacts were all associated with the forty-six year occupation of the site by Robert Nicolson. The non-reconstructability of the ceramic and glass vessels, as well as their wide date span suggests that this was not a discrete feature created expressly for the disposal of trash at a particular point in time. Rather, it appears that the ditch probably existed on the Nicolson property at some point during the last half of the 18th century. When Nicolson died and the property switched hands, subsequent cleaning of the property (ie. sweeping of the yard and cleaning of the house and basement) generated debris which was swept into the ditch. Lewis has documented this type of "abandonment refuse" behavior on Middleton Place Plantation, where reoccupation of the property after a period of vacancy was seen in large quantities of refuse recovered from a filled and sealed privy (Lewis & Haskell 1981).

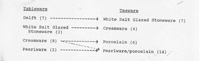

Table 1 and Figure 19 represent the quantitative data on ceramic form and type for the east yard ditch assemblage. As can be seen, over 90% of the ceramic vessels were fine tablewares, associated with dining. This, coupled with their proximity to the house, seems to suggest that this refuse was generated within the structure or a nearby kitchen. Also suggestive that the refuse was associated with the site are crossmends between ceramics in the ditch and other areas of the site.

Since this deposit obviously reflects the garbage of Robert Nicolson, owner and occupant of the property from 1751 to his death in 1797, it can be used to examine consumer behavior. Just as Nicolson's rising economic and social status is seen in his house alterations, and his purchases of luxury goods, such as books and prints, it can also be demonstrated through analysis of the ceramics within this feature.

The social status of the merchant's and tradesman's class was changing in an upward direction during the colonial period. Documentary evidence shows that Robert Nicolson was experiencing this upward mobility. Earliest records show him as a young tailor with a house and shop in the suburbs or Williamsburg. Over time, Nicolson's business improved to include such

45TABLE 1

| DELFT | JACKFIELD | WSG | CREAM | PEARL | PORC | COARSE | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tea Bowls | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Cups | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Saucers | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 12 | |||

| Plates | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 15 | ||

| Soup Plates | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Platter | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Small Bowl | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| Storage Bowl | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Chamber Pot | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Drug Pot | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 9 | 1 | 10 | 14 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 55 |

GRAPH - Figure 19. Ceramic Vessels from Eastern Drainage Ditch

GRAPH - Figure 19. Ceramic Vessels from Eastern Drainage Ditch

clientele as Governor Botetourt (Wenger 1982) and he was able to purchase a shop on Duke of Gloucester Street (YCDB 8 1769-1777:316-318). Nicolson's acceptance of public responsibilities by the Revolutionary War period indicate his status within the community. For someone of Robert Nicolson's rising status as a merchant, the tea ceremony would be expected, especially for someone who ran a "bed and breakfast" lodgings. This would call for serving lodgers tea or coffee in the morning and perhaps in the afternoon as well. Evident in Table 1 & Figure 19 is the high percentage of vessels associated with the tea ceremony. The taking of tea formed a very important social occasion in 18th century colonial America. Although the expense of tea at first limited its use to the wealthy elite, by the mid-18th century, prices had dropped and the tea ceremony became more common among the merchant classes (Roth 1961:64-66). The high number of tea-wares within the ditch may well reflect this greater use of the tea-wares and thus their increased risk of breakage.

Sine the tea ceremony did serve an important social function and was related to social status, the teaware of a household is often better quality than its tableware (Miller 1980). Also, research suggests that ceramic manufacturers first produced new ceramic styles in tea-wares. Examples of this include some shell edge tea cups and saucers produced in the 1780s and some mocha ware in the 1790s. Both of these decorative types do not exist on tea cups and saucers in the post 1800 period (Miller personal communication). Because tea and tablewares were usually purchased as separate sets in upper class households, and because the teaware was usually of a more expensive type than the tableware, there will be a limited correspondence between the two groups. Examination of the tea-wares and tablewares from the eastern drainage ditch shows that this was true. Hypotheses are made about which tea and tablewares were used contemporaneously.

As Table 1 shows, there were almost no delft tea-wares (the sole exception being a delft cup) in the ditch assemblage. This factor was primarily due to the unsuitability of delft as tea-ware, since the fragility of the glaze could not withstand repeated contact with hot liquids without cracking or breaking (Garner and Archer 1972:22). Therefore, while it is seen that although delft was used as tableware at the Nicolson House, white salt glazed stoneware was apparently serving as the teaware for the early years of Nicolson's occupation (Figure 20). Prior to the manufacture of white salt glazed stoneware plates beginning in the 1740s (Noël Hume 1969:115), porcelain, delft, and coarse earthenwares were the only ceramic alternatives for tableware. In the mid-18th century, Robert Nicolson, with his position as a tailor supplementing his income by taking in lodgers, probably could not afford Chinese porcelain. Instead, Nicolson used delft as tableware, which served at the time, as a less expensive imitation of Chinese export porcelain (Noël Hume 1968:111).

48 Figure 20. English White Salt Glazed Stoneware

Figure 20. English White Salt Glazed Stoneware

As postulated, tea-wares were likely to be seen in a newer style, with older type ceramics serving as tableware. Possible teaware/tableware combinations, for the Nicolson household as suggested by the ditch assemblage are shown below. The total number of vessels for each ceramic type are shown in parentheses.

| Tableware | Teaware |

|---|---|

| Delft (7) ---------> | White Salt Glazed Stoneware (7) |

| White Salt Glazed Stoneware (3) --------> | Cream-ware (4) |

| Cream-ware (8) [illegible] --------> | Porcelain (6) |

| Pearlware (2) --------> | Pearlware/porcelain (14) |

This table covers the period from 1751-1800. For example, cream-ware tea-wares were probably used in conjunction with white salt glazed stoneware tableware during the 1770s. The expense of porcelain precluded its general used as a tableware at the Nicolson House, as seen in Table 1 by the paucity of tableware forms. This is not true for the porcelain tea-wares, however. Porcelain teaware was probably used in the later 18th century, perhaps in conjunction with cream-ware or pearlware tablewares, as prices for porcelain dropped somewhat. The lack of tablewares in pearlware forms and the large number of pearlware tea-wares indicates that the ditch was filled and sealed prior to the extensive use of pearlware as a tableware at the Nicolson House.

In addition to ceramics, the ditch also contained 4,272 fragments of wine bottle glass. This represented 64% of the total amount of wine bottle glass found during the entire excavation. Examination of the bases and necks of the bottles shows a date range of 1740-1798 (after Noël Hume 1969, with the majority of the bottles dating between 1755 and 1788. This assemblage also falls within Nicolson's occupation of the property.

Animal species represented within the faunal assemblage of the ditch included cow, pig, sheep, fish, turkey, opossum, and white tailed deer. For complete faunal analysis, see Appendix 2.

C. Miscellaneous Features

Trash Pits

(Features 17 - 20)

A series of small features, identified as trash pits, were located along the western side of the house. These features most likely were not associated with activity occurring at the Nicolson House. Since these features were located west of the Fence-line II, they were probably associated with activity occurring on the lot west of the Nicolson House. Each small pit (ranging in north-south length from 1'3" to 2'4") was filled with a mixture of brown sandy loam and wood ash, indicating perhaps a burial of ash from fires in the structure west of the Nicolson House. Although each feature contained some small fragments of ceramics and glass, these appeared to be incidental items, swept up with the ash, and buried in holes dug specifically for the disposal of ash. Each feature seems to indicate a discrete occurrence, since they were small in size, of no consistent shape or profile. The ceramics from these features indicate they were created between 1770 and 1830.

As the features extended beyond the western limit of excavation, no true e-w measurements could be determined for any of these features. Besides ceramics typical of the 18th and early 19th centuries, these trash pits also contained small quantities of bone, oyster shell, window glass and nails. Unfortunately, no soil samples were retained which could be tested for small faunal and floral remains.

Ash Layer

Covering the area to the east of the present day bulkhead entrance was a layer of purplish-brown domestic ash. The presence of pearlware in this layer dates its deposition after 1780 (Noël Hume 1969:131), but also included was a white salt glaze stoneware dessert plate decorated with the barley pattern and a Queen's shape rim (Figure 20), dating after 1740 (Noël Hume 1969:15).

The ash layer appears to have been associated with some craft or household activity requiring a fire, occurring at the back of the house. Five small post-holes/stake holes in this area also appear to have been related to the ash. All of these post-holes 51 appear to have been formed by driving pointed stakes into the ground, with some of the holes extending 8"-10" in depth below the bottom of the ash layer. When these stakes were pulled from the ground, the holes created by their removal became filled with the domestic ash. The function of these holes is not known, but all were clustered at a distance of 3' from the south foundation wall of the house. Cream-ware in these holes dates their filling after the third quarter of the 18th century.

Agricultural Trenches

(Feature 21)

A series of shallow slots or trenches oriented in an east-west direction were evident in the front yard. These slots were very shallow, with flat bottoms, and cut through sandy sterile layers directly above natural sandy clay subsoil. These slots have been interpreted as plow scars, thus indicating the land was farmed prior to construction of the house. The only prehistoric artifact from the excavation was found in conjunction with a slot. This was a quartzite Potts variant projectile point which dated from the early to the middle Woodland period (c. 1000 B. C. to A. D. 800). No other datable artifacts were found within these features.

CHAPTER 5

CONCLUSIONS

The advent of scientific or problem-oriented archaeology has resulted in a search for patterns within the archaeological record. Patterned behavior affects the composition, form, and distribution of materials contained within the archaeological record (Binford 1968; South 1977; Redman 1978; Lewis 1976). Consequently, the discovery of patterned variation within archaeological assemblages can allow the archaeologist to formulate inferences about human behavior. Examples of this approach include Stanley South's delineations of the Carolina Artifact Pattern, the Brunswick Refuse Disposal Pattern, and the Frontier Pattern (1977), Singleton's Slave Artifact Pattern (1980) and Moore's patterning on coastal barrier island plantations (1981).

Application of this approach was difficult, however, if not impossible, at the Nicolson House due to several factors. First the limited scope of excavation did not allow for interpretation areas. Second, and perhaps more importantly, was the amount of soil disturbance around the Nicolson House foundation. Urban archaeological sites have been noted for their complex stratigraphy and extensive amounts of disturbance brought abut as a consequence of the intensive land use common to urban areas (Rothschild and Rockman 1982; Salwen 1982; Rubertone 1982). Disturbances at the Nicolson House took the forms of foundation repair, numerous utility lines, and landscaping alterations. As a result, a large amount of soil disturbance and redeposition such as these, known as site formation processes, have been discussed by Schiffer (1983: 677):

"as a result of formation processes, the archaeological record is a transformed or distorted view of artifacts as they once participated in a behavioral system."

Artifacts on urban sites are rarely recovered from their primary contexts and, therefore, patterned behavior or site organization cannot be inferred from them. The formation processes common on urban sites have created new artifact patterns, totally unrelated to past behavior (Schiffer 1983:678).

Because of the lack of undisturbed areas at the Nicolson House, this report has focused primarily on architectural features revealed through archaeological excavation. Only one artifact assemblage could be definitely associated with any one household at the Nicolson House, and most of the deposits could 53 not even be positively associated with activities occurring on the property. The most outstanding example of this was the thick layer of humus located throughout the area of excavation (Feature 13). This layer had been brought onto the site sometime in the 20th century, probably as fill.

Although the excavation revealed a good deal of previously unknown architectural information about the Nicolson House, the nature of the excavation and the amount of disturbance around the house precluded any general statements about activities occurring on the property. Much of the disturbance, ironically enough, was associated with previous attempts at halting the flow of water into the basement. Although interesting, these waterproofing attempts almost completely obliterated all evidence of the original builder's trench of the house, hindering efforts of date the house construction through artifacts contained within its fill.